Meanwhile, Ike Turner had hipped the Bihari brothers to Wolf's talents and they pacted him to RPM, setting up a session at KWEM that September that yielded Morning At Midnight( Moanin' At Midnightin paper-thin disguise), a How Many More Years variant titled Dog Me Around, and two more titles. How Many More Yearsand its eerie plattermate Moanin' At Midnightwere cut at that first date, and both pierced the R&B charts on Chess, How Many peaking higher at #4. Also on hand were drummer Willie Steele and a pianist. Accompanying Wolf was his sledgehammer guitarist Willie Johnson, a product of Lake Cormorant, Mississippi (he was born March 4, 1923) who played pretty ninth chords one second and barbed-wire leads the next.

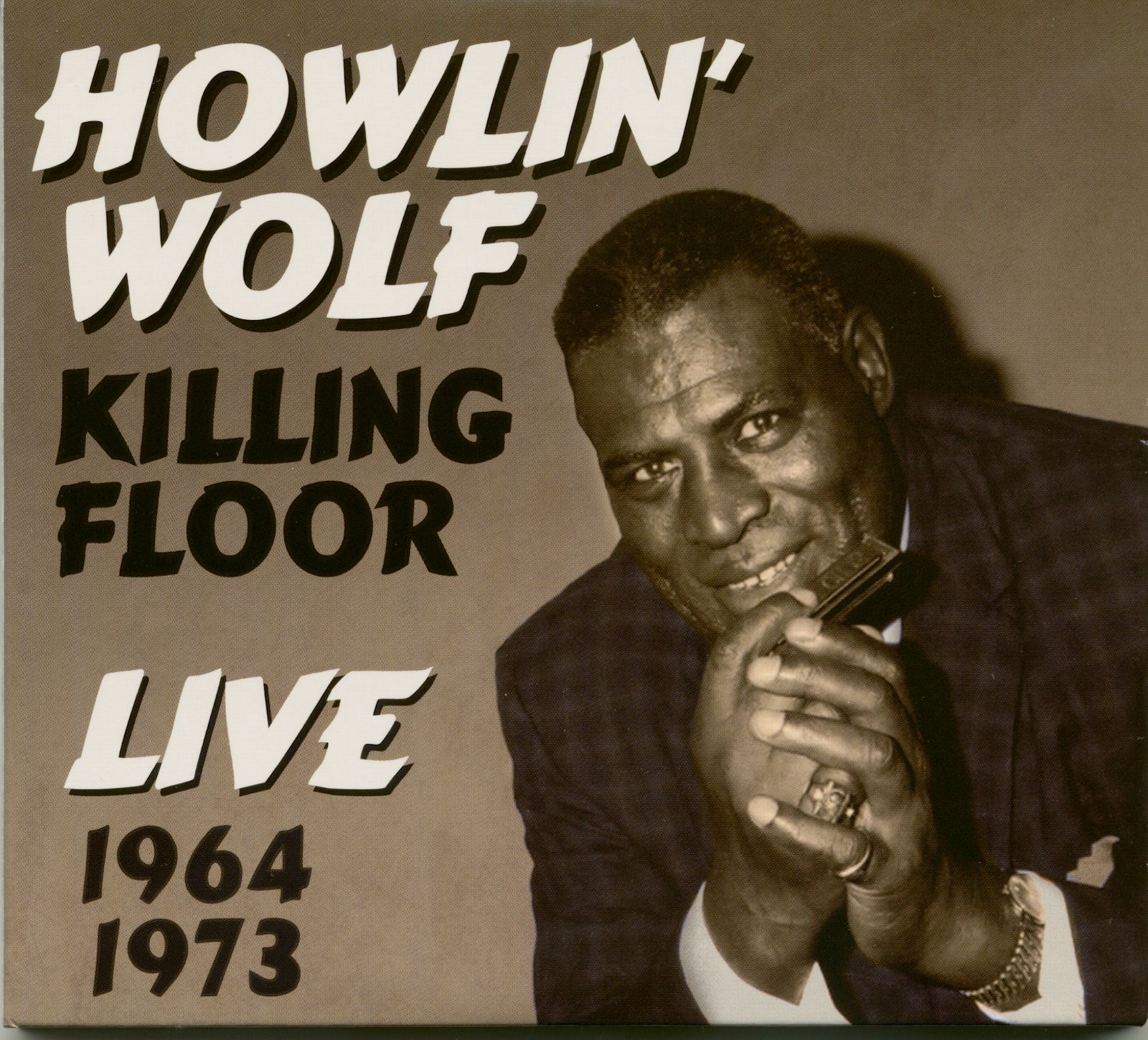

HOWLIN WOLF KILLING FLOOR FULL

Sam shipped the results up north to Chess, which requested a full session in either May or August. Phillips brought Wolf into his fledgling Memphis Recording Service in the spring of 1951 for a demo date.

Sam Phillips caught one of Wolf's broadcasts and was transfixed. After returning from an ill-fated Army stint during World War II, the big man got more serious about his music, landing a daily 15-minute program on KWEM in West Memphis in 1949. He was playing electric guitar on the streets as early as 1938. Chester picked up harmonica licks from Rice Miller-Sonny Boy Williamson #2-when the harpist was romancing Wolf's sister. His family settled in the Delta in 1923, and the great Charley Patton gave him personal tutelage on guitar in '28. That's what I respected him for."īorn Jin White Station, Mississippi (near West Point), Burnett got his stage moniker from his grandfather (the impressively built lad also answered to Big Foot and Bullcow). "Wolf was not only a musician, he was an entertainer. "Wolf was the greatest that I've ever known,"says his longtime saxist Eddie Shaw. His wheezing harmonica was as distinctive as his unbeatable flair for showmanship he routinely rolled around the stage in simulation of sexual ecstasy or climbed the stage curtains like a deranged madman. Of course, the giant known as Howlin' Wolf possessed the most fearsome, feral vocal cords in the annals of electric postwar blues. But all of the anguished lyric's malevolence is directed inward he's the one on the chopping block: "I should'a quit you, long time ago/I should'a quit you, baby, long time ago/I should'a quit you, and went on to Mexico.I should'a went on/when my friend come from Mexico at me I was foolin' with you baby/I let you put me on the killing floor.For a guy who didn't see the inside of a recording studio until he was 40 years old, Chester Arthur Burnett certainly made up for lost time. The imposing Wolf sounds like the proverbial freight train derailing.

By the time that the mighty, bellowing Wolf - an established blues star for nearly 30 years at the time of the session - opens his mouth, it becomes clear that those who follow in his wake and dare to cover the song do so at their own peril, setting a Herculean task for themselves. It is the sort of rave-up that dispels the narrator's case of the blues rather than wallowing in them. In between verses, a two-sax horn section of Arnold Rogers (tenor) and Donald Hankins (baritone) plays soul-revue stabs. Lafayette Leak pokes away eighth notes on the high register of the piano. Buddy Guy's acoustic slaps back rhythmically, rockabilly style, through tape echo. The sheer joy in the band's performance is palpable and contagious. It is all a red herring the original 1964 Chess recording of "Killing Floor" obliterates any need for covers or amalgams that use the driving riff this is the real thing. But you can't copyright a lick, as many rock & roll artists have long known, and many bluesmen were as guilty as anyone else in stealing inspiration witness, for example, the confusion over just exactly who was the real Sonny Boy Williamson. So when Zeppelin (generally among the most dubious of rock acts in the practice borrowing without acknowledging, though they do give credit here) lifted material from the masters of the genre, often they were doing so little more than five years out from an original. The guitar riff from Howlin' Wolf's foil Hubert Sumlin is instantly familiar and has been endlessly co-opted by rock acts who have stolen it for their "own" blues-rock compositions or covered it directly, as did Jimi Hendrix, Mike Bloomfield's Electric Flag, and famously by Led Zeppelin as "The Lemon Song." It is usually a surprising thing for many casual fans of the blues to hear that many such classics from Chicago, and Chess Records specifically, like well-known songs from Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, and Wolf, were recorded so late in the 1950s and '60s.

This is one of the defining classics of Chicago electric blues.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)